The immigration detention statistics published yesterday show no sign that significant and coherent detention reform is being implemented by the Home Office.

The two recent major inquiries into the state of immigration detention called for a complete overhaul of the detention system, which detains far too many people far too long. The government subsequently committed itself to detention reform.

It is not clear what progress is being made under this reform programme. The Immigration Enforcement Business Plan for 2016/17, now the year is almost over, is still unpublished. The plan to close Dungavel detention centre in Scotland was scrapped just a few weeks ago.

There are two possible speculations. One is that the reform work is taking place, but it has not translated into any tangible, positive impact yet. Another is that the process of detention reform has stalled under the Immigration Minister, Robert Goodwill.

The statistics show however that the three troubling trends continue.

Firstly, there are still a lot of people who enter the detention estate.

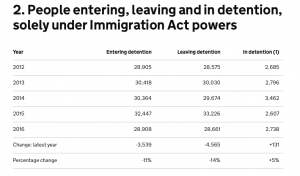

There was some reduction in the number of people entering detention: a total 28,908 people entered detention in 2016, compared to 32,447 in 2015. This is the first time since 2012 that the number fell below 30,000. We suspect that this reflects the closure of Dover IRC which took place in the last quarter of 2015 and shrunk the overall size of the detention estate somewhat.

However, overall, there has not been any huge decline in this number as the graph shows over the last few years.

(The graph was taken from this webpage.)

The gender and asylum profile of those detained has also remained more or less the same over the years. Of the 28,908 who entered detention in 2016, 14% (4,094) were female and 46% (13,230) were asylum detainees. The detention estate remains a male dominated environment, with a high number of individuals who have claimed asylum.

A rise in the number of EU citizens experiencing detention was anoted in this latest statistics release, echoing the recent media report on the same issue: there was a 24% increase in the number of EU nationals leaving detention since 2015, up from 3,647 to 4,519. Compared to non-EU nationals, a much higher percentage of EU nationals leaving detention return to their country of origin (89% as compared to 39%).

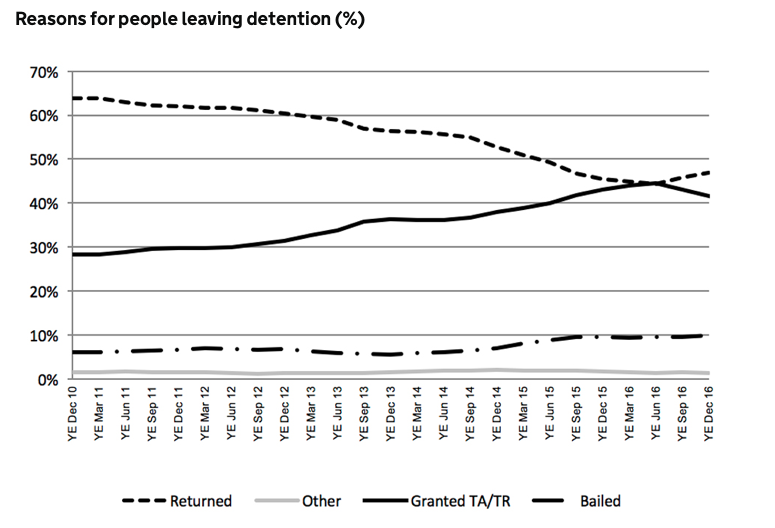

Secondly, a high proportion of people who are detained find themselves released back into the community later, raising the question of why they were detained in the first place.

While the overall number of people entering detention fell by 11% in 2016 compared to 2015, over 50% of those who leave the detention estate are not returned from the UK to their country of origin.

This follows the trend we have been seeing for a few years. For those who were detained and were released back into the community, their detention was not only harmful to their well-being but also a waste of public money.

The damaging impact of detention on individuals’ mental health and general well-being has been highlighted time and time again by those who are directly affected by detention and a range of specialist practitioners.

Immigration detention is also an expensive public policy: the cost of running the detention estate in 2013/14 was £164.4m.

(The graph was taken from this webpage.)

And lastly, many continue to experience long-term detention.

UK remains the only country in Europe to practice indefinite detention of migrants, with no set time limit at all.

The published statistics illustrates the devastating impact of this irresponsible policy: as at 31 December 2016, the longest length of time a person had been currently detained for was 1,333 days. That is three and a half years in detention. Indeed, on the same day there were 78 people who had been detained for over one year.

Such long-term detention is not an isolated incident. The same published statistics reveal that every quarter, when the snapshot picture of the detained population is taken, there is always someone who had been detained for a similar period. One caveat is that these statistics on the length of detention however do not include those detained in prisons, where extreme long detention cases are often found.

In 2016, 10,380 people were deprived of their liberty for more than 29 days (36% of the total who left detention in the year). Of these, the vast majority (62%) were released back into the community after their detention.

The Detention Forum and the Parliamentary Inquiry’s recommendation has been that the detention period should be restricted to 28 days as a maximum. This would have meant that over 10,000 would have been released from detention earlier.

Generally speaking, the longer someone is detained, more likely that they will be released from detention. Of the 208 detained for 12 months or more before leaving detention in 2016, only 29% were returned their country of origin, meaning that 72% of them returned back to the community after a lengthy period of detention, without knowing exactly when they would be released. There is a huge question over why such people were not released much earlier.

The statistics tell us nothing about the human cost of immigration detention

None of these figures, however, tells us the unique stories of individuals, their families and communities affected by immigration detention. What these figures tell us however is the massive scale of the UK’s use of detention.

So far, the slow pace of the detention reform has been disappointing. Promises have been made, but they have not translated into the statistics. To speed up this reform process, the mentality which assumes that detention is always necessary for migrants whose immigration cases have been refused must change, and change fast.

As has been said many times before, detention is harmful, many people return to their communities after detention and is expensive. There is no reason why the detention of adults cannot be substantially reduced, as has been the case for children. There is evidence to show that people can be supported in the community to continue to work on their immigration cases. Introduction of a clear time limit and development of a wider range of community-based alternatives to detention are the next steps this government should be taking.

The next set of statistics will be published in three months time. The Home Office must accelerate the speed of their detention reform, if we are to see significant reduction in the scale and the length of immigration detention. Reforming this inhumane system must be a top priority for everyone.